- Home

- Tanya Huff

The Heart of Valor Page 8

The Heart of Valor Read online

Page 8

“You’re at 670 right now, sir.”

“No . . .”

“Your drag factor is increasing marginally with every rep—671, sir.” The veins in his temples were visibly pulsing, the larger veins in his throat standing out like blue wire raising the skin. His lips were nearly purple, his lungs not up to the demand for oxygen. His hair had spiked into wet triangles. If he didn’t stop, she was ending the program.

He stopped, dropping the oars, and sagging back as the seat reconfigured as a bench. Chest heaving, his arms fell to hang limp, fingertips leaving damp circles on the mats. “I set . . . resistance . . . with no increases.”

“Then there’s a glitch in the system.” Almost everyone right out of the tanks tried to do too much too soon, but—for now—she’d give him the benefit of the doubt. She reached out as he tried to sit, sliding an arm behind his shoulders and removing it as soon it seemed he could manage on his own. The major’s data was already in her slate. Had his med-alert gone off, she’d have had a reason to keep holding on, but as it hadn’t, she’d just have to pick him up if he fell. With any luck, he’d fall straight down and hit the mats, not the deck. “I’ll tag the unit out of order; the next user might be Navy and this thing could damage their more delicate physiques.”

“That’s what I like about you, Gunny,” the major gasped. “Always considering others. I just thought . . .” He blinked down at his hand as she wrapped trembling fingers around the curve of a water bottle. “Right. Good idea. I just thought,” he began again after a long, careful swallow, “that I was out of shape. Pull started to get heavier, but, fuk, everything does.”

“Look at the bright side, sir.” Torin snapped her slate back onto her belt. “At least you know you can break a one-thirty/five-hundred-meter split.”

“Yeah, and a shorter split might have killed me.”

“Also a good thing to know.”

“In case the scenario on Crucible includes a rogue rowing machine?”

“It never hurts to be prepared, sir.” He was still flushed, but his skin was so fair it showed every little bit of color to an extreme. A better indication was the healthy pink of his lips and the way his breathing no longer sounded quite so pained. In Torin’s professional opinion, he’d live.

“Might not hurt you,” he barked, the sound clearly intended to be a laugh but not quite making it. “But I’m sure as hell going to hurt la . . .”

“This is apparently a version of taking it easy I’m not familiar with.”

Torin turned as Major Svensson stared past her at the approaching doctor. Given the apprehension on the major’s face, a Marine she’d seen use his empty KC-7 as a club to hold back an advancing squad of Others until reinforcements arrived, she was almost prepared for Dr. Sloan’s expression.

“I should stuff you back into a tank until you regenerate some common sense,” the doctor snapped. “Electrode stimulation does not rebuild the kind of muscle strength that allows you to act like a damned fool.” When he tried to stand, two fingers on his shoulder pushed him back down onto the bench. As they weren’t in a situation where it mattered, Torin preferred to believe that he didn’t resist the pressure, not that he couldn’t. “Oh, no, you’re not going anywhere until I see if you’ve done any damage.”

“Crucible,” the major began.

She cut him off, eyes locked on her slate. “We’re not on Crucible now. Nor is it likely that you’ll be out sculling and performing a repetitive series of multiple overexertions while on Crucible. I thought I made this perfectly clear right from the beginning that I’d only agree to this little adventure if you acted like a sentient species instead of a Marine.”

Torin cleared her throat.

“Present company excepted, Gunnery Sergeant. All right . . .” Eyes narrowed, she held the major in an unbreakable stare Torin found impressive even peripherally. “. . . I am going to see Dr. Weer about putting you back under his scanner so that we can compare your condition yesterday to your condition now.”

“I’m sweatier.”

“We’ll take that into account. Maintaining the tight hand grip required to hold on to an oar for extended periods of time puts the forearms at risk for overuse injuries, and as each stroke also involves twisting the oar parallel to the water with a wrist extension, you couldn’t have possibly chosen a worse exercise.”

“Or a better one to test the new arm.” He waggled pale eyebrows in her general direction.

She didn’t seem appeased. “You are going to sit here until your heart rate drops to under seventy-five beats per minute, and then you’re going to report immediately to sick bay. Gunny, I assume you have his stats in your slate. You’ll see that he stays put until seventy-five.”

“I’m sorry, Doctor, but I don’t take orders from you.” That expectation needed to be dealt with now, before things got dangerous. Torin met the doctor’s stare with one of her own.

After a long moment, Dr. Sloan sighed and nodded. “Fine. For the major’s own good, would you please keep him here until his heart rate drops below seventy-five beats a minute.”

“Yes, ma’am. As long as he doesn’t order otherwise.”

Major Svensson waved his left hand. “No, no, I’ll be good.” The nails looked a little darker than they had. Torin hoped he hadn’t damaged himself—for a number of reasons, not the least being that she really didn’t want to return to Ventris and another series of Silsviss briefings. “I did set the machine at a resistance five,” he said after the doctor left. “Not too hard a pull nor too fast a stroke.”

Back on Ventris, Dr. Sloan had mentioned memory lapses. Given that the doctor would no doubt mention them again when the major joined her in sick bay, Torin said only, “I’ve let maintenance know it needs to be looked at, sir.”

For a moment, she thought he was going to ask if she believed him, but he decided to let her comment stand.

“That looks like fun.” The major nodded at the Krai flipping back and forth among the ropes in the corner, changing the subject with all the finesse of heavy artillery. “Looks like one of those big cargo nets, doesn’t it?”

It did. Odds were good it looked just like the net on the Berganitan that had caught Big Yellow’s escape pod.

“Credit for your thoughts, Gunny. Seriously,” he added when she turned her attention back to him. “You were looking angrier than the moment demanded.”

Angry? She wasn’t angry, she was . . .

Angry.

Angry about being lied to. Angry that there was nothing she could do about it.

And a little surprised about how angry she felt.

“If you want to talk about it.” He waved a shaking hand. “I’m not doing anything at the moment but sweating.”

She hadn’t been under Major Svensson’s direct command last time they’d fought together, and it was unlikely that after the next twenty days she’d ever be under his command again. They had very little personal history and, after two tendays on Crucible, likely no personal future. But for all that, they shared a remarkably similar past and looked forward to more of the same: combat and the Corps. She respected him as both a Marine and an officer. If he was willing to listen, then maybe she should talk.

Anger clouded judgment.

Clouded judgment got Marines killed.

There was no point in mentioning the escape pod; the major would have no reason to know about a piece of classified salvage he hadn’t personally brought in. But then, it wasn’t really about the escape pod anymore.

“Major, do you ever wonder if the Elder Races are screwing us over?” She was amazed by how conversational the question sounded, none of the anger leaking out.

Or maybe, given Major Svensson’s expression, she was slightly delusional. “Us?”

“Human, di’Taykan, Krai.” In the pause, one of the Krai in the far corner dropped about two meters from rope to rope, catching himself by his feet as his companions yelled insults. “Soon the Silsviss.”

“Screwing u

s over how?”

“Manipulating data. Patronizing the Younger Races. Only telling us what they think we need to know.” Removing information they don’t want us to have. How paranoid was she to believe that making such a statement aloud was not a good idea? Rhetorical question.

“That’s a bit more than a one-credit thought, Gunny.”

“Yes, sir.” The rote response helped her regain control of her voice.

He leaned forward, arms resting on his legs, water bottle dangling from one hand. “We, the Younger Races, have full representation in Parliament.”

“Yes, sir.”

“The Elder Races promised us the stars if we’d just channel our aggression at their enemies, and they’ve kept that promise.”

“Yes, sir.”

“However, it’s interesting to note that not one of the diplomatic attempts to negotiate an end to this war have ever included a member of the three races actually fighting this war. Since hostilities started before we got involved—and my we equals your us—all we have is the Elder Races’ word for it that they don’t know why the Others are fighting.”

Behind Torin’s completely neutral expression, her thoughts charged this way and that, searching for a hard target. Suddenly, she felt a lot less personally paranoid.

Major Svensson smiled and stood. “At a certain point in the rebuilding process, they have to give your brain conscious control over parts of the process, so they wake you up. I had time to do a lot of thinking . . . speculating. So, the answer to your question is, it’s entirely possible. Unfortunately, there’s no way we—where we still equals your us—can ever be sure what the Elder Races are up to, so since we’re in it up to our eyeballs, we might as well just keep doing our jobs.” Reaching a hand under his shirt, he rubbed at the sweat drying on his stomach. “Now, what’s interesting to me is that you haven’t been spending quality time at the chop shop with nothing to do but think and encourage cell division so something had to have prompted your question. Care to tell me what it was?”

“I’d rather not, sir. Not without proof.”

“That anger’s not going to distract you from doing your job?”

“No, sir.”

“Because if there’s a chance it may, you need to deal with it. And I mean deal, not just lock it away—that does no one any good.”

He was right. Stirring things up couldn’t put the Confederation any more at risk than the Elder Races already had. She straightened, not quite coming to attention. “Yes, sir.”

“How’s my heart rate?”

“Seventy-six, sir.”

“Close enough. Let’s go see if I’m still cleared to play silly buggers with the children.”

* * *

“Northern Hemisphere Section 19 is temperate and currently two months into a four-to-five-month winter. The temperature will not vary much beyond five degrees below zero and five degrees above. As the environmental controls in our combat uniforms are good to five degrees lower and forty degrees higher, why are you now being issued with cold weather liners?” Staff Sergeant Beyhn scanned his platoon and sighed. “Go ahead, Kichar, before you rupture something.”

“Sir, Marines must be able to fight without tech in case the Others take the tech out, sir!”

“You think we’ll keep her,” Major Svensson murmured as the sergeant began to go over the details of the cold weather gear with the recruits.

Torin finished adjusting the fit of the new liners in her boots and straightened. “Kichar? Not likely, sir. She’ll do her tour, then she’ll spend the rest of her life talking about how her time in the Corps was the best part of her life. She’ll talk a lot about how people who didn’t serve won’t understand—which is true enough about some things but will have bugger all to do with most of what she’ll be referencing. She’ll join a veteran’s organization and organize the shit out of it. Eventually, she’ll run it.”

The major grinned. “Seems harmless.”

“Unless she’s heading for officer’s training, sir.”

His grin broadened. “I’ve had second lieutenants just like her.”

“Did they survive their second battle?”

He opened his mouth and closed it again while Torin piled hat and gloves on top of her folded bodyliner. Years in it had given her enough familiarity with the one-piece garment. She was able to pull gear for both herself and the major she knew would do, leaving only the bootliners to be fitted. It was one thing if a sleeve was a bit long and another thing entirely for footwear to go wrong. Marines were infantry. They used their feet.

Major Svensson stared thoughtfully into the crowd of half-dressed recruits. “Now I feel like we should hack Kichar’s files and direct her away from officer training if that’s where she’s headed.”

“She’ll survive a lot longer if she’s never in command,” Torin agreed, glancing over at where the recruit in question—already in her combats while most of her platoon were still working out the seals in the bodyliner—was reaching for her vest. Overachievers were only a pain in the ass until they became responsible for other lives. Then they became dangerous because they tended to demand those they led share their views. Sometimes, experience dulled down the shine a bit, and the Corps got its money’s worth. More often, because at least they led from the front, they didn’t last long.

Beyhn nodded once in approval at Kichar as he passed her—she did, after all, have the fastest gear-up time—and then continued moving among the recruits, touching a shoulder here, adjusting a seal there. He was touching a lot. That was usual for a di’Taykan, and Torin would have thought nothing of it except he seemed . . .

Fussy?

He was a lot more involved than his junior DIs, going so far as to wave Sergeant Jiir off in order to adjust a Krai bootliner himself when it would have made more sense to have Jiir do it. Torin made a mental note to make certain the Krai sergeant checked the fit later. They weren’t her platoon, but they were Marines and Krai feet with their opposable toes required a specialist’s touch.

Had the staff sergeant been so involved when she’d been training?

Actually, when she was in training, she’d been too damned intimidated to notice.

“All right.” Beyhn moved back to one end of the VTA’s troop compartment and touched the big screen. “The purpose of this exercise is to move from our drop point here to our pickup here.” A second touch and the pickup point lit green. “We’ll be covering 340 kilometers of mixed terrain—you’re getting off easy because we’ll be escorting a civilian. There are three villages en route; we may control them, we may not. During our stroll, systems representing the Others will be trying to stop us. We’ll be trying to take them out. Simple really. Even you lot should be able to do it. This map is being loaded into your slates as I speak. I’d suggest you familiarize yourselves with it, but I shouldn’t have to remind you of such basic survival prep by now, should I? Any questions?”

“Sir!” A short Human, so skinny he’d look like a mushroom with his helmet on, stepped out of the crowd. “Is it likely to snow while we’re there, sir?”

“Do I look like a weather satellite, McGuinty? There’s snow on the ground now, and it’s winter; the chances are good it’ll snow. You want to know more than that, check the data yourself.”

“Sir! Will we be able to access the actual weather satellite from the planet, sir?”

“No, you will not be able to access any of the satellites from the planet. I will. Whether I’ll bother is another question.” Half a turn and he pointed at a di’Taykan near the back. “Yeah, Ayumi.”

“Sir, do the di’Taykan have to wear the hats, sir?” A pale gray toque hung off one finger and her emerald-green hair drooped at the possibility of having to cram it on her head.

“No.” Beyhn held up his own toque. “Because we’re comfortable at lower temperatures than either the Humans or the Krai, we do not have to wear the hat; the helmet liner will be enough. However,” he continued over a ragged cheer, “we do have to carr

y them. Just in case.”

“Sir!” Pale pink hair flipped back and forth on a recruit towering over the Krai beside him. “In case of what, sir?”

“Who the hell knows; that’s the point.”

The staff sergeant sounded the way Torin remembered him.

“You will all be issued two FG3s, you’re carrying the threes because they have longer det times and that lessens the chance of some idiot losing a hand. Scouts—and this position will rotate daily—will be carrying demo charges as well. And by the way . . .” His eyes narrowed and his hair, out from his head in a scarlet corona, stilled. “. . . you will be recruits moving across country in a scouting position, you will not be Scouts. If by some miracle any of you lot turn out to be among the bare sixty percent that makes it through the eighty-day Scout course, then you can call yourselves Scouts, not before. Now . . .” His hair started moving again. “. . . since we’re a little short on heavy gunners . . .”

Heavy gunners began their training after Basic. Vids of Marines learning to use their shiny new exoskeletons and destroying government property in a variety of amusing ways invariably showed up in the SRM.

“. . . the fourth member of every fireteam will be issued with the KC-9.” Beyhn reached behind his back and pulled the weapon out of a locker, blind. It looked impressive, but Torin saw he’d positioned himself to make it impossible to fail—it never hurt to give perceived omnipotence a hand. “You’ll remember this from your time on the range,” he continued. “I know you’ve only fired a few rounds, but if you’re qualified on the seven, you can fire this. Bigger and heavier than the KC-7, recruits who carry it tend to have a shortened life expectancy in combat, so you’ll be switching off daily. Some Marines like it better than the 7; there’s no accounting for taste.”

“Sir, why do recruits who carry the KC-9 end up as early casualties, sir?”

“Did you miss the part about it being bigger and heavier, Piroj?”

“Sir, no, sir!”

“Does it come with augmentation?”

“Sir, no, sir!”

“Then you know the reason. And take your hat off.”

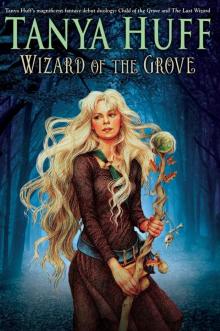

Child of the Grove

Child of the Grove Blood Lines

Blood Lines What Manner of Man

What Manner of Man Blood Pact

Blood Pact Blood Debt

Blood Debt The Wild Ways

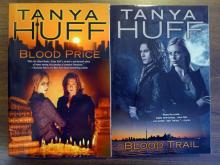

The Wild Ways Blood Trail

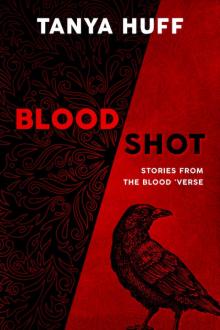

Blood Trail Blood Shot

Blood Shot Wizard of the Grove

Wizard of the Grove Valor's Trial

Valor's Trial The Privilege of Peace

The Privilege of Peace A Peace Divided

A Peace Divided Three Quarters

Three Quarters The Heart of Valor

The Heart of Valor No Quarter

No Quarter The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar

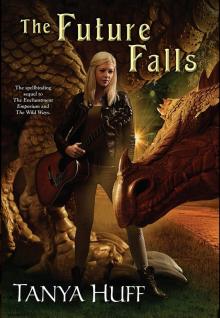

The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar Enchantment Emporium

Enchantment Emporium 3 Blood Lines

3 Blood Lines The Heart of Valour

The Heart of Valour Smoke and Ashes

Smoke and Ashes 2 Blood Trail

2 Blood Trail 1 Blood Price

1 Blood Price Summon the Keeper

Summon the Keeper The Future Falls

The Future Falls Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World

Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World The Second Summoning

The Second Summoning Fifth Quarter

Fifth Quarter The Enchantment Emporium

The Enchantment Emporium An Ancient Peace

An Ancient Peace Blood Bank

Blood Bank February Thaw

February Thaw The Better Part of Valour

The Better Part of Valour The Silvered

The Silvered Valour's Choice

Valour's Choice Smoke and Shadows

Smoke and Shadows Sing the Four Quarters

Sing the Four Quarters 4 Blood Pact

4 Blood Pact Long Hot Summoning

Long Hot Summoning The Better Part of Valor

The Better Part of Valor Scholar of Decay

Scholar of Decay He Said, Sidhe Said

He Said, Sidhe Said Wild Ways

Wild Ways Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light

Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light Valor's Choice

Valor's Choice Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan

Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan