- Home

- Tanya Huff

Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light

Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light Read online

Praise for Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light

“Contemporary urban fantasy at its best.”

—Locus

“An enlightened, compassionate view of the forgotten heroes of urban society.”

—Library Journal

“A tale with sweep and scope, interesting characters, and some impressively nasty menaces.”

—Booklist

“Huff’s sense of fun as she plays with the traditional elements should please even the most jaded of readers.”

—Charles de Lint

Praise for The Fire’s Stone

“The delightful camarderie of three unlikely heroes and well controlled fantasy elements make Huff’s adventure great fun to read.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Huff arranges the ordinary elements of fantasy into an extraordinary tale of adventure and transformation.”

—Library Journal

“An exciting adventure … they face pirates, storms, traitors … each has unique talents that can bring their mission to a successful conclusion, each has weakness that could destroy themselves and a city of people.”

—Voya

Also by

TANYA HUFF

BLOOD PRICE

BLOOD TRAIL

BLOOD LINES

BLOOD PACT

BLOOD DEBT

*******

SING THE FOUR QUARTERS

FIFTH QUARTER

NO QUARTER

THE QUARTERED SEA

*******

SUMMON THE KEEPER

THE SECOND SUMMONING

*******

WIZARD OF THE GROVE

*******

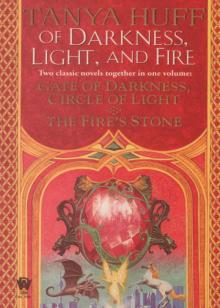

OF DARKNESS, LIGHT AND FIRE

*******

VALOR’S CHOICE

THE BETTER PART OF VALOR*

*coming soon from DAW Books

GATE OF DARKNESS, CIRCLE OF LIGHT

Copyright © 1989 by Tanya Huff

THE FIRE’S STONE

Copyright © 1990 by Tanya Huff

OF DARKNESS, LIGHT, AND FIRE

Copyright © 2001 by Tanya Huff

All Rights Reserved.

The Bait and The Wind’s Four Quarters are both copyright © 1985

by Firebird Arts and Music

Cover Art by Paul Youll

DAW Book Collectors No. 1206.

DAW Books are distributed by Penguin Putnam Inc.

All characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to persons living or dead is strictly coincidental.

If you purchase this book without a cover you should be aware that this book may have been stolen property and reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher. In such case neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.”

First Paperback Printing, December 2001

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

GATE OF DARKNESS, CIRCLE OF LIGHT

For Kate.

For the future.

THE FIRE’S STONE

For Uncle Albert, who know what family means.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I’d like to thank Hania Wojtowicz, the Metropolitan Toronto Police Department, the University of Toronto Archives, and Dr. Douglas Richardson at University College for their help and patience.

I’d also like to thank Mercedes Lackey for generously allowing me to use both The Bait and The Wind’s Four Quarters.

Gate Of Darkness, Circle Of Light and The Fire’s Stone are, respectively, the third and fourth books I wrote. Seventeen books later, they’re still two of my favorites. Why? Well, to begin with they’re both totally self-contained. You don’t have to read books before or after either or them in order to get the entire story. (In spite of a loyal Fire’s Stone readership that continues to plead for a sequel.) Secondly, these were the books where I actually started feeling like I knew what I was doing; that as well as being able to tell a story (which I never doubted) I could construct characters and build plot and bring both to a logical and stirring conclusion. Finally, they’re both good stories.

Even though I wasn’t entirely certain these two books belonged together—one is contemporary fantasy, the other a more traditional quest fantasy—I am glad that DAW believed in them enough to give them a second life, a second chance to reach the shelves of the world’s bookstores.

I guess you can tell that I’m not one of those writers who can’t bear to read her early work. I like my early work. I hope you do too.

—Tanya Huff

July 2001

Chapter One

“Rebecca!”

Rebecca paused, one hand on the kitchen door.

“Did you put your tins away neatly?”

“Yes, Lena.”

“Have you got your uniform to wash?”

Rebecca smiled but otherwise remained frozen in the motion of leaving. Her food services uniform was folded neatly in the bottom of her bright red tote bag. “Yes, Lena.”

“Do you have your muffins for the weekend?”

“Yes, Lena.” The muffins, carefully wrapped, were packed safely on top of her soiled uniform. She waited for the next line of the litany.

“Now, don’t forget to eat while you’re home.”

Rebecca nodded so vigorously her brown curls danced. “I’ll remember, Lena.” One more.

“I’ll see you Monday, puss.”

“See you Monday, Lena.” Freed by the speaking of the last words, Rebecca pushed open the door and bounded out and up the stairs.

Lena watched her go, then turned and went back into her office.

“And you go through this every Friday, Mrs. Pementel?”

“Every Friday,” Lena agreed, settling down into her chair with a sigh. “For almost a year now.”

Her visitor shook his head. “I’m surprised she’s allowed to wander around unsupervised.”

Lena snorted and dug around in her desk for her cigarettes. “Oh, she’s safe enough. The Lord protects his own. Damn lighter.” She shook it, slammed it against the desk, and was rewarded by a feeble flame. “I know what you’re thinking,” she said, as she sucked in smoke. “But she does her job better than some with a lot more on the ball. You’re not going to save any of the taxpayers’ money by getting rid of her.”

The man from accounting frowned. “Actually, I was wondering how anyone could continue smoking given the evidence. Those things’ll kill you, you know.”

“Well that’s my choice, isn’t it? Come on,” she rested her elbows on the desk and exhaled slowly through her nose, waving the glowing end of the cigarette at his closed briefcase. “Let’s get on with it …”

“They cut emeralds from the heart of summer.”

The grubby young man, who’d been approaching with the intention of begging a couple of bucks, hesitated.

“And sapphires drop out of the sky, just before it gets dark.” Rebecca lifted her forehead from the pawnshop window and turned to smile at him. “I know the names of all the jewels,” she said proudly. “And I make my own diamonds in the refrigerator at home.”

Ducking his head away from her smile, the young man decided he had enough on his plate, he didn’t need a crazy, too. He kept moving, both hands shoved deep in the torn pockets of his jean jacket.

Rebecca shrugged, and went back to studying the trays of rings. She loved pretty things and every afternoon on the way home from the government building where she worked, she lingered in front of the window displays.

Behind her, the bells of Saint James Cathedral began to call the hour.

“Time to go,” she told her reflection in the glass and smiled when it nodded in agreement. As she walked north, Saint James handed her over to Saint Mic

hael’s. The bells, like the cathedrals, had frightened her when she’d first heard them, but now they were old friends. The bells, that is, not the cathedrals. Such huge imposing buildings, so solemn and so brooding, she felt couldn’t be friends with anyone. Mostly, they made her sad.

Rebecca hurried along the east side of Church Street, carefully not seeing or hearing the crowds and the traffic. Mrs. Ruth had taught her that, how to go inside herself where it was quiet, so all the bits and pieces swirling around didn’t make her into bits and pieces, too. She wished she could feel something besides sidewalk through the rubber soles of her thongs.

At Dundas Street, while waiting for the light, a bit of black, fluttering along a windowsill on the third floor of the Sears building, caught her eye.

“No, careful wait!” she yelled, scrambling the sentence in her excitement.

Most of the other people at the intersection ignored her. A few looked up, following her gaze, but seeing only what appeared to be a piece of carbon paper blowing in the wind, they lost interest. One or two tapped their heads knowingly.

When the light changed, Rebecca bounded forward, ignoring the horn of a low-slung, red car that was running the end of the yellow light.

“Don’t!”

Too late. The black bit dove off the window ledge, twisted once in the air, became a very small squirrel, and just managed to get its legs under it before it hit the ground. It remained still for only a second, then darted to the curb. A truck roared by. It flipped over and started back to the building, was almost stepped on and turned again to the curb, blind panic obvious in every motion. It tried to climb a hydro pole, but its claws could get no purchase on the smooth cement.

“Hey.” Rebecca knelt and held out her hand.

The squirrel, cowering up against the base of the pole, sniffed the offered fingers.

“It’s okay.” She winced as the tiny animal swarmed up her bare arm, scrambled through her hair, and perched trembling on the top of her head. Gently she scooped it off. “Silly baby,” she said, stroking one finger down its back. The trembling stopped, but she could still feel its heart beating against her palm. Continuing to soothe it, Rebecca stood and moved slowly back to the intersection. As the squirrel was too young to find its way home, she’d have to find a home for it, and the Ryerson Quad was the closest sanctuary.

The Quad was one of Rebecca’s favorite places. Completely enclosed by Kerr Hall, it was quiet and green; a private little park in the midst of the city. Very few people outside the Ryerson student body knew it existed, which, Rebecca felt, was for the best. She knew where all the green growing places hid. This afternoon, with classes finished for the summer, the Quad was deserted.

She reached up and gently placed the squirrel on the lowest branch of a maple. It paused, one tiny front paw lifted, then it whisked out of sight.

“You’re welcome,” she told it, gave the maple a friendly pat, and continued home.

A huge chestnut tree dominated the small patch of ground between the sidewalk and Rebecca’s building, towering over the three stories of red brick. Rebecca often wondered if the front apartments got any light at all but supposed the illusion of living in a tree would make up for it if they didn’t. Stepping onto the path, she tipped back her head and peered into the leaves for a glimpse of the tree’s one permanent inhabitant.

She spotted him at last, tucked up high on a sturdy branch, legs swinging and head bent over the work in his hands; which, as usual, she couldn’t identify. All she could see of his face were his eyebrows which stuck out a full, bushy, red inch under the front edge of his bright red cap.

“Good evening, Orten.”

“’Tain’t evening yet, still afternoon. And my name ain’t Orten, neither.”

Rebecca sighed and crossed another name off her mental list. Rumplestiltskin had been the first name she’d tried, but the little man had merely laughed so hard he’d had to grab onto a branch.

“Well, hello, Becca.” The large-blonde-lady-from-down-the-hall stepped through the front door, thighs rubbing in polyester pants.

Rebecca sighed. Nobody called her Becca, but she couldn’t get the large-blonde-lady-from-down-the-hall to stop. “My name is Rebecca.”

“That’s right, dear, and you live here at 55 Carlton Street.” Her voice was loud and she pronounced each word deliberately, a verbal pat on the head. “Who were you talking to?”

“Norman,” Rebecca ventured, pointing up into the tree.

“Not likely,” snorted the little man.

The large-blonde-lady-from-down-the-hall pursed fuchsia lips. “How sweet, you’ve named the birds. I don’t know how you can tell them apart.”

“I don’t talk to birds,” Rebecca protested. “Birds never listen.”

Neither did the large-blonde-lady-from-down-the-hall.

“I’m going out now, Becca, but if you need anything later don’t you hesitate to come and get me. She brushed past the girl, beaming at this opportunity to show herself a good neighbor. That Becca may not be right in the head, she’d often told her sister, but she’s so much better mannered than most young people. Why, she never takes her eyes off me when I speak.

For almost a year now, Rebecca had been trying to decide if the white slabs of teeth between heavily painted lips were real. She still couldn’t make up her mind, the volume of the words kept distracting her.

“Maybe she thinks I can’t hear?” she’d asked the little man once.

His answer had been typical.

“Maybe she doesn’t think.”

She fished her keys out of her pocket—her keys always went in the right front pocket of her jeans, so she always knew where they were—and put them in the lock. Then she thought of a new name and, leaving the keys dangling, went back to the tree.

“Percy?” she asked.

“You wish,” came the response.

She shrugged philosophically and went inside.

Friday night she did-the-laundry and had beef-vegetable-soup-for-supper, just as she was supposed to according to the list Daru, her social worker, had drawn up. Saturday, she spent at Allen Gardens helping her friend George transplant ferns. That took all day because the ferns didn’t want to be transplanted. Saturday night, Rebecca went to make tea and found she was out of milk. Milk was one of the things Daru called odds and ends groceries and she was allowed to buy it herself. Taking a dollar and a quarter out of the handleless space shuttle mug, she let herself out of the apartment and walked down Mutual Street to the corner store. She didn’t stop to talk to the little man, nor to even look up into the tree. Daru had said over and over she had to be careful with money and she didn’t want to hold on to it any longer than she had to.

Hurrying back, she wondered why the evening had grown so quiet and why the poorly lit street suddenly seemed so filled with shadows she didn’t recognize.

“Mortimer?” she called when she reached the tree, knowing he would answer whether she guessed his name or not.

A drop of rain hit her cheek.

Warm rain.

She put up her hand and it came away red.

Another drop crinkled the paper bag around the milk.

Blood.

Rebecca recognized blood. She had bleeding once a month. And Daru had said that any other time but then blood meant something was wrong and she was to call her no matter when, but Daru wouldn’t see the little man and he was the one bleeding, Rebecca knew it, but she didn’t know what to do. Daru had said she must never climb trees in the city.

But her friend was bleeding and bleeding was wrong.

Rules, Mrs. Ruth had often said, exist to be broken.

Putting down the milk, she jumped for the bottom branch of the chestnut. Bark pulled off under her hands, but she tightened her grip—people were always surprised at how strong she was—and swung herself up, kicking off her thongs. Men in orange vests had tried to take that branch off earlier in the spring, but she’d talked to them until they forgot why they were there an

d they’d never come back. Rebecca didn’t approve of cutting at trees with noisy machines.

She climbed higher, heading for the little man’s favorite perch. The dusk and the shifting leaves made it hard to see, throwing unexpected patterns of shadow in her way. When her hand closed over a wet and sticky spot, she knew she was close. Then she saw a pair of dangling boots, the upturned toes no longer cocky as blood dripped off first one and then the other.

He had been wedged into the angle formed by two branches and the main trunk. His eyes were closed, his hat was askew, and a black knife protruded from his chest.

Carefully, Rebecca lifted him and cradled him against her. He murmured something in a language she didn’t understand but otherwise lay completely motionless. He weighed next to nothing and she could carry him easily in one arm as she descended, his legs kicking limply against her hips, his head lolling in the crook of her neck.

When she reached the bottom branch, she sat, wrapped her other arm about her wounded friend, and pushed off. The landing knocked her to her knees. She whimpered, then got up and staggered for the safety of her apartment.

Once inside, she went straight to the bed alcove and laid the little man upon the double bed. Around the knife his small chest still rose and fell so she knew he lived, but she didn’t know what she should do now. Should she call Daru? No. Daru wouldn’t See so Daru couldn’t help.

“She’ll think I’m slipping again,” Rebecca confided to the unconscious little man. “Like she did when I told her about you at first.” She paced up and down, chewing the nails of her left hand. She needed someone who was clever, but who wouldn’t refuse to See. Someone who would know what-to-do.

Roland.

He hadn’t ever actually said he could See. He’d hardly ever said anything to her at all, but he spoke with his music and the music said he’d help. And he was clever. Roland would know what-to-do.

She sat down on the edge of the bed and pulled on her running shoes, then turned and patted the little man on the knee.

Child of the Grove

Child of the Grove Blood Lines

Blood Lines What Manner of Man

What Manner of Man Blood Pact

Blood Pact Blood Debt

Blood Debt The Wild Ways

The Wild Ways Blood Trail

Blood Trail Blood Shot

Blood Shot Wizard of the Grove

Wizard of the Grove Valor's Trial

Valor's Trial The Privilege of Peace

The Privilege of Peace A Peace Divided

A Peace Divided Three Quarters

Three Quarters The Heart of Valor

The Heart of Valor No Quarter

No Quarter The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar

The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar Enchantment Emporium

Enchantment Emporium 3 Blood Lines

3 Blood Lines The Heart of Valour

The Heart of Valour Smoke and Ashes

Smoke and Ashes 2 Blood Trail

2 Blood Trail 1 Blood Price

1 Blood Price Summon the Keeper

Summon the Keeper The Future Falls

The Future Falls Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World

Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World The Second Summoning

The Second Summoning Fifth Quarter

Fifth Quarter The Enchantment Emporium

The Enchantment Emporium An Ancient Peace

An Ancient Peace Blood Bank

Blood Bank February Thaw

February Thaw The Better Part of Valour

The Better Part of Valour The Silvered

The Silvered Valour's Choice

Valour's Choice Smoke and Shadows

Smoke and Shadows Sing the Four Quarters

Sing the Four Quarters 4 Blood Pact

4 Blood Pact Long Hot Summoning

Long Hot Summoning The Better Part of Valor

The Better Part of Valor Scholar of Decay

Scholar of Decay He Said, Sidhe Said

He Said, Sidhe Said Wild Ways

Wild Ways Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light

Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light Valor's Choice

Valor's Choice Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan

Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan