- Home

- Tanya Huff

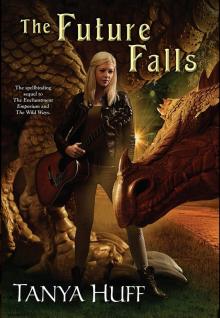

The Future Falls Page 25

The Future Falls Read online

Page 25

“So you want us to save the rest of world, little Wyrm?”

“No. We want to know if you’re going to.” He nodded toward the crests on their jackets. “Me, I kind of thought you might want a chance to save basketball. We’re not going to do it. We’re still arguing about saving hockey.”

Elessar and Arwen locked gazes for a moment, then Elessar dumped another three packages of sugar into his coffee and said, “There’s that.”

“We will discuss this information among ourselves.” Arwen inclined her head in what was clearly a dismissal.

“Good for you. Then let me know what you decide to do, so I can take it to the aunties and make sure there’s no misunderstandings.” And she did not dismiss him. Who was the prince here anyway? “Are you going to eat that?” He nodded toward her nearly untouched pie.

She pushed it to him.

“Thanks.”

“It’s poisoned.”

Jack shrugged. “Dragon.” If they were that easy to kill, he’d have fewer uncles.

They watched him eat, watched him stand, watched as Joe fell into step beside him and the two of them left the diner. It wasn’t until they were across the road and nearly to Joe’s car that Jack finally felt the weight of their combined gazes drop off.

“You might want a chance to save basketball?” Joe asked.

Jack opened his mouth, belched, and melted a no parking sign.

“HOW LONG DO WE WAIT?”

Charlie shifted on the chaise and lifted her face toward the sun, barely visible behind a scud of clouds. The apartment had been empty when they got back so there was no need to hide out on the roof, but given how often Jack had switched to scales lately, she figured he’d be more comfortable outside. Because it was all about Jack and not at all about how she’d started to feel trapped within the well-charmed walls. She needed to see what was coming.

They’d barely stayed inside long enough to fill bowls with sesame ginger chicken, kept warm in Allie’s big crockpot, and slide biscuits into their pockets.

At least it had stopped raining.

“Charlie?”

“If they don’t get back to us in the next twenty-one and a half months, I suggest we say fuck ’em.”

“Not helpful. Nor funny,” he added.

If the Courts couldn’t help—no, if the Courts actually admitted they couldn’t help, which wasn’t the same thing, Charlie realized—then there was no reason for Jack to slip into the past and spend four miserable years learning sorcery. They were one step closer to not being able to stop the world from ending, but, bottom line, the world ending should be misery enough. She didn’t need to look at Jack and see four unnecessary years of pain. “Ow.” Rubbing her arm where he’d poked her, she turned to see him sitting on the edge of the second chaise, feet on the deck beside the empty bowls, staring down at her, expression entirely unrepentant. “What?”

Jack shrugged. “You were wearing your I was forced to listen to Justin Bieber face. What are you thinking about?”

“The Courts.” How convenient, not a lie.

“And how if they can’t help, then there’s no reason for me to go learn from them.”

Not a question. So Charlie asked one, “How did you get that out of a I was forced to listen to Justin Bieber face?”

He didn’t return her smile. “If they can’t, or won’t stop the asteroid, it doesn’t mean that I wouldn’t be able to if I was trained. I’m unique, remember. Gale. Dragon Prince. Sorcerer. Wild Power. One of a kind. All bets are off.”

“I’d never bet against you.” The words slipped out before she could stop them.

“But you don’t want me to go.” Before Charlie could say anything—and since she couldn’t deny it, she had no idea of what to say—he added, “Even though you go away all the time.”

Unfortunately, there wasn’t even a hint of sulky teenager in his voice she could respond to and use to avoid the actual issue. “I’ve never gone away for four years.”

“It won’t be four years to you.”

She couldn’t do this lying down. Shoulders raised against the chill that crept in the moment she moved her body away from the charms on the chaise, she sat up, tucked her knees to the right of his, and said, “Jack, if you came back before you left, I’d still know that you’d been gone for four years. Ignoring the top forty emo way I’d feel every moment of every year here . . .” She touched her chest. “. . . while it was happening and I’d see them in every way they’d changed you. Not that you were four years older,” she added hurriedly before he could speak, “but the price you paid. I hate the thought of you suffering for any reason. Even to save the world.”

“Yeah.” He shrugged. “But it’s my decision.”

The urge to yell, “You’re seventeen!” was intense. Charlie sat on it. “I know. And if it comes to it, if it’s our last shot to save the world, I’ll take you back.” His leg jumped under her hand. His pulse matched hers. “But if it turns out that the Courts can’t stop the asteroid, what exactly can they teach you besides a totally useless three point layup?”

He stared at her hand for a moment, then met her gaze, his eyes gold. “They can teach me how to be a sorcerer, and I can figure the details out myself. My father was more powerful than any of them.”

The first few notes of what Charlie thought might be Leonard Cohen’s “To a Teacher” started up, but she shut it down before she could be certain. “How do you figure that?”

“He slept with my mother and survived.” And the subtext said, Duh.

“Valid point.” Forcing herself to break the contact, she lifted her hand off his knee, and leaned back. “Although, you don’t know that the entire Court is unable to match your father’s success . . .” If Jack was going to split hairs, she’d split a few back at him. “. . . only that none of them have tried.”

“And that proves they’re not all hair and attitude. My mother is very beautiful and very powerful and very dangerous and she’d eat any member of the Court who tried to approach her. They’d never discover if they were powerful enough to survive actual sex.”

What counted as inactual sex? Charlie wondered. “She didn’t eat your father.”

“Gales,” he said, his tone suggesting Charlie was being deliberately dim, “are charming.”

“True.”

“And they have a reputation to back up the charm.”

“We.”

“What?”

Charlie caught his gaze and held it. “We have a reputation to back up the charm.”

He snorted. “Your phone is ringing.”

It took her a moment to realize that the snort and the statement were unconnected. “Probably Allie,” she muttered digging it out of her pocket, “figuring she’d given me enough space. Or Auntie Gwen having spoken to Joe or . . .”

“I want to see my grandchildren.”

“Auntie Mary?”

“Did you hear what I said, Charlotte?”

“I did. Don’t you think that’s a bit risky, considering there’s barely a week before ritual?” With David anchoring first circle, it would be safest for all concerned if Auntie Mary stayed half a continent away from her only son until there was a lot less horn in the mix.

“Don’t talk to me about risk, Charlotte. If the world’s going to end . . .”

“I guarantee it’s not going to end before ritual.”

“And do you guarantee that I’ll be able to travel after ritual? After what Jane has planned for this ritual?”

Charlie spent a moment wondering what Auntie Jane had planned, then decided she didn’t want to know.

“Actually . . .” Auntie Mary sounded distinctly triumphant. “. . . can you guarantee you’ll be able to travel after ritual?”

Really, really didn’t want to know.

* * *

Once in

the Wood, it wasn’t hard for Charlie to tease Auntie Mary’s song out of the aunties’ chorus; it still held much of the old familiar melody and a measure or two that reminded her of Allie. Once, there’d been measures that reminded her of David, but not anymore. Any tie David still had to his mother would not be maternal.

Charlie was a little surprised to step out of the Wood into the old orchard and see Auntie Mary beckoning to her from the porch. She’d expected a quick turnaround before Auntie Jane had a chance to point out, at length, what a bad idea this was.

“Auntie Ruby’s asking for you. I told her I was going,” she added as Charlie reached the house, “in case she had a message to pass on to Allie or the boys.”

“And she asked for me?”

“It was the most coherent she’s been for about five days.”

Auntie Ruby’s bedroom was on the first floor, in one of the earliest additions to the old farmhouse. The walls were a yellow so bright even October couldn’t dim them, rag rugs covered most of the exposed linoleum floor, and an ancient quilt did what it could to hide the entirely practical hospital bed. She had her own small bathroom and a low wide window that looked over the east flowerbeds where the asters remained untouched by frost and provided drifts of color shading from white to deep purple. When Auntie Ruby finally died, another elderly auntie would inherit both the space and the care that came with it.

Auntie Meredith and a plump tabby both looked up when Charlie entered surrounded by a cloud of allspice and cinnamon drifting in from the kitchen, but only Auntie Meredith stood. Knitting gathered up into a messy bundle, she leaned close as she passed and said softly, “See if you can convince Ruby to move on. There’s a lot of work to do before impact.”

“You’re very calm about it.”

“Don’t be ridiculous, Charlotte, death is a part of all things.”

“I meant about the impact.”

Auntie Meredith patted her arm. “My observation stands. And I’m so sorry to hear about you and Jack. So good that there’s plenty going on to distract you.”

She was gone, trailing a double line of pale blue yarn, before Charlie could respond.

“That’s why I didn’t want them to know,” she muttered at the cat. “The world’s ending, and it’s still going to be, ‘Oh, poor Charlie.’”

The cat yawned.

Moving to Auntie Ruby’s side, Charlie realized she had no idea if the skin that had collapsed around the old woman’s prominent bones looked like actual parchment, but she’d seen enough cookies baked to recognize parchment paper just out of the oven—brittle, fragile, and stained by use. She couldn’t hear a heartbeat, only a soft flutter, and each breath sounded like the last breath.

Until one of them sounded like her name.

“I’m here, Auntie Ruby.”

Auntie Ruby’s eyes had sunk deep. It seemed as if half the lashes were missing from the edges of pinkish purple lids, and the whites were a sort of yellow/gray. For all that, they were surprisingly aware.

“Thing left . . . to do.”

“What thing, Auntie Ruby?” All things considered, Charlie wasn’t really surprised when the dying woman found the strength to sneer. “Okay, none of my business. What can I do?”

“Delay . . .”

“Dying? You want me to delay your death? I’d be happy to, if only to annoy Auntie Meredith, but I don’t know how. Death delaying isn’t exactly a Wild Power. Death defying, yes. Delaying, not so much.”

It wasn’t exactly an eye roll, but it was close enough and Charlie had years of experience in eye roll interpretation.

“You’re saying I do know how? I just need to figure out what I know.” Telling her not to die, in a Bardic sort of way, would not end well. Although, the odds were high that zombie aunties would ensure the world welcomed an extinction event, so . . . lemons to lemonade.

“Delay . . .”

“Right. Don’t stop, delay.” She settled on the edge of the bed and decided it might be safer not to stroke the cat. Auntie Ruby had been old for as long as Charlie could remember—old and crazy and good for embarrassing stories about other members of the family if caught on her own. She’d cackled and not cared who heard her and, if she got her hands on a broom, she was all about reliving her glory days. It was hard to see the woman in the bed as the Auntie Ruby of memory. She’d faded until . . . “Holy crap, your fingers are cold!” The contrast between her wrist and the single finger pressed against it nearly burned.

“Hum . . .”

“I’m humming? Sorry. I do that when I think. The whole don’t stop thing made me think of Fleetwood Mac and don’t stop thinking about tomorrow and yesterday’s gone and . . .”

Auntie Ruby found strength enough to raise the remains of both eyebrows up a centimeter.

“. . . and yesterday isn’t gone, is it? Not yet. It’s all right here.” Charlie laid her hand gently on Auntie Ruby’s arm, drew in a breath of air so acidic it caught in the back of her throat, and Sang. Remember the time you painted Surrender Dorothy on the water tower? Remember how Auntie Jane always makes the tea too strong? Remember moving with Uncle Edward in ritual? Remember sisters and nieces and cousins. Remember the sweet/tart taste of cherry pie. Remember. Remember. Remember. This isn’t who you were, this is who you are.

* * *

Auntie Jane was waiting outside the door.

“It wasn’t my idea. Auntie Ruby asked me to delay her death.” Given Auntie Jane’s expression, it seemed smart to get the melody down fast. “All I did was redefine her life.”

“All you did? All?”

Objectively, given that in under twenty-two months an enormous asteroid was going to slam the planet to ratshit, Auntie Jane shouldn’t have been all that scary. Realistically, Charlie’d never heard of anyone able to be objective about the aunties.

“Yesterday,” Auntie Jane continued, “she asked me to remind Raymond to stop at the cheese factory, and yet I didn’t hold a séance to pass that on. She’s dying, Charlotte. Her mind spends more time on the other side than it does here and she doesn’t know what she’s asking.”

Charlie considered the need she’d seen in Auntie Ruby’s eyes. “This time, I think she did.”

“You think? You sing!”

“Not mutually exclusive, Auntie Jane.” She stepped sideways, opening up a line of escape through the dining room and into the kitchen, but, for the moment, didn’t take it. “Maybe Auntie Ruby wants to cross over with her cousins, a part of the final chorus.” Even if they could branch the family again, Auntie Jane would be among those staying in Darsden East, tied too tightly to the place to leave. Every word Auntie Jane spoke resonated with that knowledge and not even Auntie Jane could be entirely unaffected by a countdown to death. Accept it, yes. Remain unaffected, no. The undertones were remarkably similar to Gary’s. With a little less bouzouki.

“Maybe,” Charlie added, “she wants to be a pain in the ass, one last time.”

“That,” Auntie Jane snorted, “I believe. Well, come on, then. Mary’s waiting in the kitchen. We’re canning some pumpkin before we start another set of pies.” She turned expectantly, so Charlie fell into step beside her. “Your mother’s garden had some lovely pie pumpkins this year. Stop by and see her when you bring Mary back. I’m trusting you to keep her away from David should Alysha’s boy babies scramble her mind.”

“Is that likely to happen?”

“Who knows? The women in this family have a complicated relationship with their boys. Scarcity adds value. An appalling number of us have the same attraction power, not to mention poor impulse control, the first of us did. That said, I assume Jack informed you that I want the two of you participating in ritual a week Wednesday. No fourth circle nonsense.”

Air quotes from the aunties were always frighteningly definitive. Mouth primed to say no, Charlie met Auntie Jane’s dark-on-dark gaze and heard

herself say, “What?”

“We’re not leaving either your power or his out of a possible solution.”

Charlie stopped in the kitchen doorway and stepped back into the dining room, shooting an insincere smile and wave at the aunties, aunts, and cousins around the table ladling steaming pumpkin puree into jars. The asteroid had poked a stick into an anthill, and until the ritual freed them from hope, the aunties, aunts, and cousins were doing what Gales did when they had time to kill. “What’s this about a solution? You and Auntie Bea actually agreed—with each other—that the aunties can’t stop the asteroid.”

“Possible solution,” Auntie Jane repeated. “We don’t know what the whole family working together can do until we try. When this is over, however over ends up being defined, I want no one able to say that we didn’t try everything.”

She hadn’t been able to argue about that with Jack. Couldn’t argue with it now. “Okay. What if Jack stays in Calgary and I come here?”

“You’re staying in Calgary.” Standing on the worn threshold, Auntie Jane turned her back on the kitchen and dropped her volume from commanding to we can pretend not to hear this. “Katie can’t handle Jack. You can. I realize this will make your personal complicated relationship even more so, but we’re trying to stop the world from ending and, as your sisters say, it sucks to be you.”

“You talked about this with my sisters?”

“They were referring to you and Jack in general, not the upcoming ritual in particular.”

“Small mercies,” Charlie muttered. It wasn’t pity. That was something.

“If you don’t want to participate, Charlotte, you have an option.”

“I do?”

“Save the world before next Wednesday.”

And given that the subtext added a terrifyingly sincere, which I’m quite sure you could do if you only put your mind to it, Charlie had nothing to say.

“Look at how big they’ve gotten!” Releasing Allie, from a second or possibly third extended hug—Jack had lost count—Auntie Mary bent to lift one of the twins off the floor. “And this one’s Evan . . . ?”

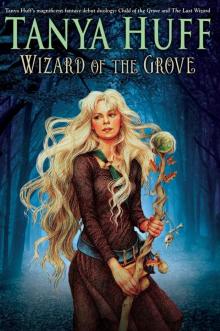

Child of the Grove

Child of the Grove Blood Lines

Blood Lines What Manner of Man

What Manner of Man Blood Pact

Blood Pact Blood Debt

Blood Debt The Wild Ways

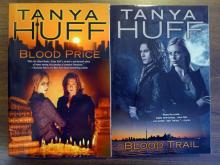

The Wild Ways Blood Trail

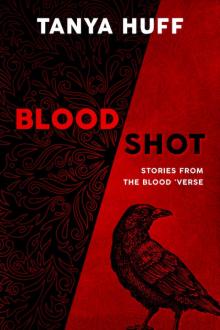

Blood Trail Blood Shot

Blood Shot Wizard of the Grove

Wizard of the Grove Valor's Trial

Valor's Trial The Privilege of Peace

The Privilege of Peace A Peace Divided

A Peace Divided Three Quarters

Three Quarters The Heart of Valor

The Heart of Valor No Quarter

No Quarter The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar

The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar Enchantment Emporium

Enchantment Emporium 3 Blood Lines

3 Blood Lines The Heart of Valour

The Heart of Valour Smoke and Ashes

Smoke and Ashes 2 Blood Trail

2 Blood Trail 1 Blood Price

1 Blood Price Summon the Keeper

Summon the Keeper The Future Falls

The Future Falls Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World

Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World The Second Summoning

The Second Summoning Fifth Quarter

Fifth Quarter The Enchantment Emporium

The Enchantment Emporium An Ancient Peace

An Ancient Peace Blood Bank

Blood Bank February Thaw

February Thaw The Better Part of Valour

The Better Part of Valour The Silvered

The Silvered Valour's Choice

Valour's Choice Smoke and Shadows

Smoke and Shadows Sing the Four Quarters

Sing the Four Quarters 4 Blood Pact

4 Blood Pact Long Hot Summoning

Long Hot Summoning The Better Part of Valor

The Better Part of Valor Scholar of Decay

Scholar of Decay He Said, Sidhe Said

He Said, Sidhe Said Wild Ways

Wild Ways Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light

Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light Valor's Choice

Valor's Choice Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan

Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan