- Home

- Tanya Huff

Scholar of Decay Page 24

Scholar of Decay Read online

Page 24

“Can you see my sword?”

“You have a sword?” The boy’s eyes widened. He dove off the bed and did a whirlwind search of the room. “There’s no sword here,” he concluded at last, voice and expression an accusation.

“I had a sword when I got here.”

“Maybe Tante Louise took it away. I’ll go look for it for you.”

“Why would Louise take away my sword?”

Jacques paused at the door and turned around to face the bed again, one eyebrow cocked. “You’re not very old are you?”

“I’m twenty,” Dmitri told him, confused.

“Uh-huh. I’m ten.”

As the door closed behind him, Dmitri had the strangest feeling the boy knew something he didn’t. Something he didn’t, but should.

“Sir, please, you must eat.”

“Go away.”

“You have barely eaten or slept since you returned from that house, sir. You will be able to help neither of them if you fall ill.”

With ink-stained fingers, Aurek pushed a strand of filthy hair back off his face. “I have much work to do and little time to do it in. Leave me alone.”

“Sir …”

“Edik.” He lifted bloodshot eyes off the parchment sheets spread across the desk and turned just enough to see the bulky shape of his servant outlined in the door to the bedchamber. “I said, leave me alone.”

Edik’s sigh said enough to fill volumes. After a pregnant pause, he bowed and retreated. Aurek knew he wouldn’t go far, but distance was unimportant as long as he went. He’d rarely had to raise his voice to Edik, unlike Dmitri …

Dmitri.

How could he have done such a thing? How could he have given Natalia to that contemptuous vermin?

The quill in his right hand bent and finally snapped as his fingers curled into fists. Irritably throwing the ruined pen onto the floor, Aurek’s gaze ended up, as it always did, on the alcove and the empty pedestal.

How could Dmitri have done such a thing?

Well, he didn’t know what he was doing, did he? chortled the hateful voice in his head. You never saw fit to tell him about the results of your arrogance. You were the great scholar, and knowledge was your power. You were too blind to see that knowledge is powerful only when you use it. Your arrogance, your blindness, trapped your precious Natalia.

Aurek ground his knuckles against his temples. “Shut up,” he snarled.

You know, you might get further if you asked yourself why he took the little lady. Maybe he was trying to get your attention. Maybe he had something to say to you, and it was the only way he could get you to listen. The voice twisted itself into an edged parody of concern. Now, why would he think that, I wonder?

“You know nothing about this,” Aurek ground out through clenched teeth. “Nothing!”

The laughter swelled until it beat against the inside of his skull, pounding and pounding and pounding as though it were determined to break free. You blind and arrogant fool! I know everything you know!

“You know NOTHING!”

“Sir?”

“Go away, Edik!” With trembling fingers, Aurek dipped a fresh quill into the dish of ink and began to write. Once he’d had a hundred spells at his command, a hundred spells collected and bound into a single volume. Some were so simple they barely needed to be written down. Some were so complicated they barely could be written down. Some were original. Some variations. He’d studied them all—studied them, learned them, inscribed them, and gone on. He’d almost never used them, unless it became necessary to clarify the details of a gesture or a material component. He thought of himself as a scholar, not a wizard.

“A scholar.” His own bitter laughter joined the echoes in his head. A wizard would have thought first of the power he’d collected and protect it. He’d thought only of his scholarship, and it had destroyed his life.

He stared down at the words he’d written, pushed the parchment aside, and began again. Once he’d had a hundred spells. He didn’t have them now. He needed to re-create, out of memory, a spell to hold a wererat captive, a spell to hold Jacqueline Renier. He had to be a wizard now, or his Natalia would die.

And your brother? How fortunate that you warned him of what he was getting into. If I’d blithely allowed my brother to become involved in a wererat power struggle, I’d be feeling pretty guilty right about now.

Calling up his last reserves of strength, Aurek pushed the voice to the back of his mind and buried it under memory. Dmitri had been lost—tragically and irrevocably lost—when he’d given Louise Nuikin what she wanted. No matter what the wererat said, he doubted his brother had lived even a moment after handing over the figurine.

“How did you persuade Dmitri to go along with this? Did you convince him that you loved him?”

“I didn’t have to. I merely convinced him that you didn’t.”

Just as his Lia had, Dmitri had paid for his blind arrogance. But there was still a chance to save Natalia, and grief would have to wait. As Aurek worked, he could still hear faint reverberations of the laughter, but he’d grown almost used to that.

The lamp on the corner of the desk sputtered. Shadows danced maniacally about the room. Snorting impatiently, Aurek reached out and turned up the wick. He didn’t have time to tend to insignificant details, but when the flame leaped up in answer to his touch, he stared at it, suddenly mesmerized by the light.

“Something to burn the darkness away,” he murmured, leaning wearily toward it.

Then, in its white depths, he saw a familiar face under a wild shock of gray hair. Pale eyes gleamed under heavy lids, and thin lips stretched into a cruel smile.

“NO!”

The lamp’s clay bowl smashed against the mantel, burning oil spilling down over the brick and across the hearth. Flames danced out onto the wooden floor, and the planks began to smolder.

That’s it, laughed the hateful voice. Burn the darkness away.

Aurek sighed and stretched out his hands to the blaze. He was just too tired to do anything about it. And the warmth felt so good.

Then he jerked back as a man-shaped shadow leaped into the room, viciously slamming a folded blanket down on the fire. A moment later, he could smell burning wool and feel large hands close around his upper arms. The smoke made it hard to see and caused his eyes to water so badly tears ran freely down both cheeks.

“Edik?”

“I’m here, sir. The fire’s out. Come, I have a bath drawn for you and a light supper prepared, and then you’ll sleep for a while.”

He allowed himself to be lifted to his feet and led from the study. He didn’t have the strength to protest. “Edik?”

“Yes, sir?”

“I never meant to hurt him. I never meant to hurt either of them.”

“Master Dmitri made his own choices, sir. You are not solely responsible for his fate.”

“And hers?”

When Edik made no reply, Aurek listened to the laughter instead.

“Jacqueline?” Marri Renier advanced timidly into the drawing room holding a folded piece of paper in front of her like a shield. Why the head of the family had decided to stay with her, she had no idea, but it made her very nervous. Scarred in a sibling battle she’d barely won, she’d moved to Mortigny to live a quiet life away from family power struggles and, while she appreciated the honor of having Jacqueline in her house, she didn’t appreciate the undercurrent of terror that came with her. These last few weeks as Jacqueline had searched for the human, Henri Dubois, Mortigny had not been a pleasant place—though that had actually been kind of fun. “Jacqueline, this just arrived from Pont-a-Museau.”

When Jacqueline stretched out an imperious hand, Marri dropped the paper into it and scuttled away to stand by the door, curiosity keeping her in the room.

Ignoring her cousin, Jacqueline glanced down at the wax seal. She didn’t recognize which of the commercial scriveners the seal belonged to but, if she correctly interpreted the bloody claw prints scratche

d on the paper beside it, whoever had sent the message had also taken care it would never be repeated. The family put little trust in promises of confidentiality.

She cracked the seal and moved closer to the candles on the mantel as she unfolded the single sheet. After a moment, she began to laugh.

“What is it?” Marri asked, encouraged by Jacqueline’s amusement.

“You can always count on family,” Jacqueline told her, still chuckling as she dropped into a wingback chair. “If they find a chance to stab someone in the back, they’ll jump at the opportunity. And if they don’t find a chance, they’ll create one. It’s so nice to see my trust was not misplaced.”

“You were expecting this note?”

“I was expecting a note. If not this one, then another.” Black silk rustled as a rat crept out from under Jacqueline’s skirts and climbed up to perch on the arm of the chair. Her expression hardened as she lightly stroked the top of its head with one finger. “Bring me paper, pen, and ink,” she said. “I think I’ll let my dear sister know when she can expect me to arrive home.”

“Jacqueline will be back early on the day of the ball. I knew she wouldn’t miss an opportunity to be the center of attention.” Louise looked up from the letter on her lap and studied Aurek Nuikin, the minimal candles burning in the chateau library sufficient for were-sight. His pale blond hair had been pulled back into a dull and dirty tail, and his beard appeared to have turned more gray than gold. Ink stains made black blemishes over both hands. His eyes were bloodshot. “Frankly, you look terrible. Are you certain you’ll be able to fulfill your part of the bargain?”

“And if I’m not able?”

Louise smiled unpleasantly, the civilized, conversational tone falling from her voice. “Then I’ll think you’re not trying. Perhaps I should send you bits of your brother as incentive. It’s amazing how many bits a strong young man can lose and still live.” Reading his thoughts from his expression, her smile broadened. “You think I’ve already killed him, don’t you? Perhaps I’ll send you a bit to prove I haven’t.”

Hope rose unbidden, and with it, a warning. “If Dmitri is harmed …”

“You’ll do what I ask anyway—you know it, I know it, and I assume your wife, if she knows anything at all in that exquisite little prison of hers, knows it too.” Leaning back in the chair, Louise crossed her legs, silk skirts whispering secrets. “You know what you have to do and when, so I don’t think it’s necessary for us to meet again.”

Aurek’s eyes narrowed. “It wasn’t necessary for us to meet tonight.”

“Not necessary, no. But I do so enjoy having a powerful wizard at my beck and call.” She dropped her chin and peered flirtatiously up at him through her lashes. “Or do you think it’s unladylike for me to gloat?”

A muscle jumped in his jaw as Aurek spun on one heel and stomped toward the door. With his hand against the worm-eaten wood, he paused and half turned. “Your sister has no doubt been told of your comings and goings and of your guests.”

“I know.” Louise stood, and her fingertips brushed over the notch in her ear. “But what can they tell her? That young Dmitri has moved into the guest chambers, and his older brother has come to the chateau to try to convince him to come home? I doubt very much that she’ll care. While distraught relatives aren’t exactly frequent visitors to the chateau, neither are they unheard of. As long as you both remain unhurt, I have done nothing for her to complain of. Had she objections to my relationship with your brother, she’d have voiced them when it began.” She took a step toward him and, though she didn’t actually change, her features suddenly appeared sharper, more menacing. “And if you decide to tell her what’s going on, I guarantee I’ll know about it, and your family will become significantly smaller.”

“I’m not a fool,” Aurek growled.

“Not a fool?” she repeated, with a serrated laugh. “Only a fool would have allowed his relationship with his brother to have deteriorated to the point where that brother became a threat. Especially when that poor, sweet brother so desperately wanted to be friends.” Watching her accusation cut into his heart, she twisted the knife. “I used the tool you forged for me, wizard.”

He stared bleakly at her for a long moment, then bowed his head and left the room.

“I found your sword.”

Dmitri jerked out of a light doze and stared in confusion at the slight figure silhouetted in candlelight beside the bed. “Jacques?”

“Of course,” the boy replied impatiently. “And I said, I found your sword.”

“My sword?” Dmitri pushed himself up so that he reclined against the pillows in a half-sitting position. “You found my sword,” he repeated. “Thank you. Where was it?”

“In the trophy room.” Responding to the unaffected enthusiasm in Dmitri’s smile, the boy’s mouth curved tentatively in return. “It didn’t have a scabbard though. And it’s pretty dirty.” He reached down, grabbed the leather-wrapped hilt in both hands, and heaved the heavy blade up onto the bed. Bits of dried blood flaked off onto the coverlet. “Have you killed many people with it?”

“Only one.” Dmitri’s expression sobered. “A man insulted one of my sisters, and I fought a duel with him.”

Jacques eyes gleamed. “Was it exciting?”

“Very exciting.” The smile flashed again as he remembered, then faded as he remembered further. The man’s family—more embarrassed by Dmitri’s relative youth than outraged by the actual death—had been about to declare cmepte chorosh, death debt, when Aurek had suddenly appeared, and the extended feud had not occurred. He had no idea of what Aurek had done, but their sisters had insisted he’d saved Dmitri’s life.

He was probably more worried about his stupid studies being disturbed by my funeral, Dmitri told himself bitterly, since he didn’t think I was worth even a quick two words of explanation. Now that he knew Aurek was a wizard, it explained a lot.

“What are you thinking about?” Jacques demanded, unused to being ignored.

“My brother.”

“You have a brother and a sister?”

“I have four sisters.”

Jacques sighed, thin shoulders lifting and falling melodramatically. “I have only me.”

“You must have lots of cousins,” Dmitri offered. It seemed a fair guess as nearly everyone he met professed to be one of the Renier family.

“It’s not the same as having a brother.” His nose wrinkled as he pointed at the sword. “That’s wererat blood. You didn’t kill a wererat did you?”

“It attacked me—” Dmitri began, but the boy cut him off.

“Mama is not going to like that. She says …” He paused and rearranged what his mama said so that he wasn’t giving anything away. “She says only wererats can kill wererats.”

The child looked so serious and disapproving that Dmitri found himself protesting. “I didn’t exactly kill it. We fought, and it fell into a giant spider’s web.”

“So the spider killed him?”

“I didn’t actually see …” The wererat’s screams rose up for a moment in memory. “Yes.”

“That’s all right then.” He climbed up onto the end of the bed, folded his legs, and declared, “I like you. There are too many women around here.”

Dmitri grinned and scratched at the bristles on his chin. Four older sisters gave him a good idea of what life must be like for Jacques. “You can come and visit me anytime. I’d be glad of the company.” He glanced toward the lines of night visible through the closed shutters. “But isn’t this a little late? Shouldn’t you be in bed?”

“No!”

The boy looked so scornful, Dmitri had to hide a laugh in a fit of coughing.

Jacques studied the human thoughtfully and wondered if he’d tell him what Tante Louise was up to. Probably not. No one ever told him anything. Chantel wouldn’t tell him either, even though he’d met her every evening at the attic window. Actually, he rather suspected from the frantic way she was acting that Chantel didn’

t know either, and she desperately wanted to. Maybe the human—Dmitri—would tell Chantel. She was older. Although not, Jacques amended silently, as much as she thought she was. If he brought Chantel here, he could listen from the next room—there were holes that went almost all the way through the wall. And then I’d know something that no one would know that I knew. He frowned as he worked through the tangles. I’m sure I could use that against someone. His mama always said that knowledge was power. She would be so proud of him.

“Do you know my cousin Chantel?”

Surreptitiously rubbing at his stained blade with a corner of the coverlet, Dmitri started guiltily. “Yes. I do. She’s a … friend.”

“Would you like me to bring her to see you?”

“Could you?” His voice sounded a little wistful. Although Louise came by as often as she could, none of his new friends had come to see him, and he’d been feeling forgotten about and sorry for himself.

“ ’Course I could. Or I wouldn’t have asked.”

The corners of Dmitri’s mouth twitched at the indignant answer. “Then yes, I’d like to see her.”

Jacques nodded solemnly. “Then I’ll bring her.”

“Jacques! What are you doing in here?”

Jacques threw himself off the bed, whirling around to face the door in the same motion. “Tante Louise!”

Eyes narrowed dangerously, Louise advanced into the room. “I asked you a question, Jacques.”

“I was visiting Dmitri.” He sidestepped out of her direct path. “I brought him his sword.”

“His what?” Surprise stopped Louise in her tracks.

“My sword,” Dmitri put in from the bed. “Please don’t be angry with the boy,” he pleaded, sounding not a lot older than Jacques. “I asked him to bring it.”

The boy? Jacques shot an indignant glare at the bed. How dare the human refer to him in such a way!

“I’m not angry with him.” Louise stepped forward again, the hem of her skirt marked with the dust of her passage through the east wing. She smiled down at her nephew and then extended the smile to include Dmitri. “I just don’t want him to tire you.”

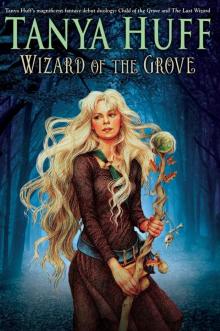

Child of the Grove

Child of the Grove Blood Lines

Blood Lines What Manner of Man

What Manner of Man Blood Pact

Blood Pact Blood Debt

Blood Debt The Wild Ways

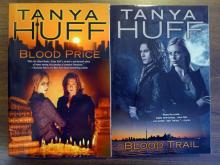

The Wild Ways Blood Trail

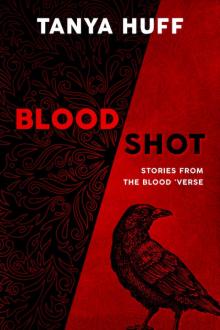

Blood Trail Blood Shot

Blood Shot Wizard of the Grove

Wizard of the Grove Valor's Trial

Valor's Trial The Privilege of Peace

The Privilege of Peace A Peace Divided

A Peace Divided Three Quarters

Three Quarters The Heart of Valor

The Heart of Valor No Quarter

No Quarter The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar

The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar Enchantment Emporium

Enchantment Emporium 3 Blood Lines

3 Blood Lines The Heart of Valour

The Heart of Valour Smoke and Ashes

Smoke and Ashes 2 Blood Trail

2 Blood Trail 1 Blood Price

1 Blood Price Summon the Keeper

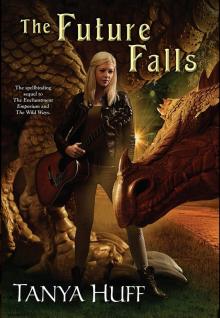

Summon the Keeper The Future Falls

The Future Falls Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World

Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World The Second Summoning

The Second Summoning Fifth Quarter

Fifth Quarter The Enchantment Emporium

The Enchantment Emporium An Ancient Peace

An Ancient Peace Blood Bank

Blood Bank February Thaw

February Thaw The Better Part of Valour

The Better Part of Valour The Silvered

The Silvered Valour's Choice

Valour's Choice Smoke and Shadows

Smoke and Shadows Sing the Four Quarters

Sing the Four Quarters 4 Blood Pact

4 Blood Pact Long Hot Summoning

Long Hot Summoning The Better Part of Valor

The Better Part of Valor Scholar of Decay

Scholar of Decay He Said, Sidhe Said

He Said, Sidhe Said Wild Ways

Wild Ways Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light

Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light Valor's Choice

Valor's Choice Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan

Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan