- Home

- Tanya Huff

Wild Ways Page 2

Wild Ways Read online

Page 2

What was she playing? She had to pick out another four bars before she recognized it. “‘One.’ It’s Metallica.”

“I know it. I hold my breath as I wish for death. Oh, please, God, wake me.” Donna met Charlie’s eyes in the rearview mirror, and grinned. “Trapped in a broken body, begging for release. And I thought country music was depressing. Problems, chica?”

“No, everything’s good. It’s just where my fingers fell.” Because everything was great. The band was getting some solid recognition, their EPs selling well enough that Tony was talking about them taking it full time and touring outside of Alberta and Saskatchewan. More Gales were moving west to Calgary and, as much as she enjoyed staying with Allie and Graham, Charlie’d been thinking of getting her own place. There’d been rumors that the apartment over the coffee shop next door to the Emporium would be available sometime in the fall and she couldn’t think of anything more perfect. She’d gain a little privacy while changing almost nothing about how she lived.

“Broken Wings?” Donna’s question jerked her out of her thoughts. Apparently, her fingers had moved on without her. “Chica, I wasn’t suggesting you play depressing country music. I mean, sure, there’s nothing like starting the day with a song about a woman trapped in a . . . Shit!” Swerving onto the shoulder, she somehow missed the car suddenly in their lane trying to pass an oil truck headed north.

Charlie hit a quick A minor 7th and managed to get all four wheels back on the pavement.

“Know any songs about assholes on the road?” Donna wondered after they’d spent a moment or two remembering how to breathe.

Charlie could feel a faint buzz under her skin. As though the adrenaline rush had plucked a string with its action set too low. “I know a few . . .”

Almost eight and a half hours and an uncounted number of assholes slowing them down later, they reached Edmonton. An hour after that, pulling out of a gas station onto highway 2 on the south side of the city, Charlie gripped the bus’ steering wheel and smiled. She could feel Calgary, feel the branch of the Gale family newly anchored there tugging at her. Anticipating home, she could almost ignore the lingering buzz.

“Fifty says I can make it to Tony’s place in less than three.”

Before anyone could point out that a legal speed would take closer to four hours, Jeff, the bass player, took her up on it.

Two hours and forty-seven minutes later, they unloaded the essentials off the bus in Tony’s driveway.

“If I hadn’t seen it,” Jeff muttered, handing over a twenty and three crumpled tens, “I wouldn’t have believed this hunk of junk could make a lateral move across four lanes of traffic at one twenty.”

“I didn’t think it could do one twenty,” Tony grunted, loading the last of his drum kit onto the bus’ old wheelchair lift. “All right . . .” He straightened and stretched, twisting the knots out of his back, damp streaks of darker gray staining his pale gray T-shirt. “ . . . since I’m pretty sure you lot are as sick of the sight of me as I am of you, let’s give it a couple of days, and say Tuesday evening for the debrief at Taylor’s place.”

Taylor waved a finger but allowed the offer of her apartment to stand.

Weighed down with two guitars, her mandolin, her banjo, and a duffel bag of dirty laundry, Charlie waved an entire hand and then staggered down the driveway to where one of the younger members of the family had left her car.

“Allie, it could easily be stupid o’clock in the morning when we get in.”

“Yeah, and they have these things called phones, you know. You could call when you’re close.”

Gale family phones began as the cheapest pay-as-you-go handset available, spent quality time with the aunties, and finished as free, reliable cell service—where reliable meant the aunties saw no reason to allow an absence of signal to interfere with their need to meddle. In the right liver-spotted hands, tech sat up and begged.

Charlie’d rolled her eyes in her cousin’s general direction. “Or you could just have one of the kids drop my car off at Tony’s Sunday afternoon.”

Given that their younger cousins considered the car theirs while Charlie was touring, they’d gone with the second option.

Embracing the clichés of playing in a country band, she’d intended to buy a pickup, but safely transporting more than one instrument at a time turned out to be more important than a faux redneck image. Sitting behind the wheel, everything securely stowed, Charlie sighed and glanced up at her reflection in the rearview mirror. “I have a station wagon.”

Her reflection wisely did not point out that the amount of crap she’d accumulated required a station wagon.

She used to store her extra instruments at her parent’s place, dropping by to grab what she needed when she needed it.

She used to travel with her six string and a clean pair of underwear stuffed into a pocket on her gig bag. Some days, the underwear had been optional. The roads she used to take had no traffic, no GPS location . . .

“No idiot driving like a gibbon with hemorrhoids!” she snarled, finally managing to get around the SUV driving 10K under the limit while hugging the center line.

No Gale ever said driving like an old lady. Old ladies in the Gale family drove like they owned the roads. And the other drivers. And the local police department. And the laws of physics.

Roaring up the ramp onto Deerfoot, Charlie felt the city tuck itself around her. It was nice. There was nothing wrong with nice.

Glancing over at Nosehill Park, she searched the curve of the hill for the silhouette of a ten point stag. Even passing at 110K, she could feel the power radiating from both the ancient and current ritual sites, but there was no sign of David. It wasn’t like she’d expected to see him. He’d been spending more time on two feet lately and, for all she knew, he’d headed into town for a beer.

With the change under control, he’d been talking about finding some consulting work. Everyone felt a job would help him regain the scattered pieces of his Humanity where everyone, for the most part, meant Allie, who still felt irrationally guilty about her part in her brother’s transformation into the family’s anchor to this part of the world. Charlie figured it had been a fair trade for saving said world, but David wasn’t her brother and Allie . . . Well, Charlie loved her, but Allie had a habit of holding on just a little too tight.

Three weeks ago, just after the Midsummer ritual and before the band had left on this latest mini tour, Charlie’d spent some time with David in the park and he’d seemed fine to her. He’d been managing weekly dinners with Allie and Graham at the apartment over the Emporium, with Katie at Graham’s old condo, and with Roland and Rayne and Lucy at Jonathon Samuel Gale’s old house in Upper Mount Royal. Plus variable members of the family being a given in each case. Over the last year, three sets of Gales—couples of Charlie’s generation—had transferred from the Toronto area to equivalent jobs in Calgary, and bought houses next to each other on Macewan Glen Drive. It wouldn’t be like it had been back in Darsden East when Charlie was growing up, when the Gale girls had run the schools from kindergarten to college, but it was a start.

Gale boys were too rare to be allowed out alone, but they couldn’t run a ritual without at least one in the third circle, so Cameron, now heading into his second year at the University of Alberta, had been sent west with six of the girls on his list, carefully picked by the aunties to be distant enough cousins to eventually cross to second circle with him. Charlie hadn’t bothered keeping track of the girl cousins who’d come and gone and returned and reconsidered. Cameron’s list, Roland’s list, David’s list—Gale girls flocked around Gale boys like bees around flowers.

Fortunately, only three aunties were required for a first circle. Although nine short of a full circle, three were enough to keep things going, particularly when backed by Allie’s second circle why yes, I can do scary things level of power. After that whole saving the world thing, Auntie Bea and Roland’s grandmother, Auntie Carmen had gone back to Ontario only long enough to pack up th

e essentials and have an extended meeting behind closed doors with Auntie Jane. No one could tell Charlie what had been said, but no one doubted Auntie Bea and Auntie Carmen were Auntie Jane’s eyes on the ground.

When they’d returned to Calgary, they’d been the first to buy property on Macewan Glen Drive as two of the twenty-five houses overlooking the park had gone on the market the moment they’d made it clear they were interested. They currently lived together in the smaller of the two and rented the other to Cameron and the girls. Cameron had the basement apartment and got in a lot of practice recharming the lock on his door.

Auntie Gwen remained in the apartment over the Emporium’s garage, refusing to share her leprechaun.

Charlie’d spent most of the time she wasn’t with the band helping the family get settled in and agreeing, as graciously as she could, to retrieve treasures forgotten in Ontario.

The buzz returned, running across her shoulders. She nearly spun out on the off ramp trying to scratch the itch it left behind.

At nine thirty on a Sunday night, 9th Avenue was empty enough that Charlie could make the left turn onto 13th Street without pausing. She parked in the alley behind the Emporium, noted what looked like a new scorch mark on the wooden siding, grabbed her guitar, charmed open the small garage door, and squeezed through to the inner courtyard. Extending the space to put Graham’s truck and Allie’s car under cover without collapsing the loft upstairs had required impressive charm work.

Charlie couldn’t have done it.

But then Charlie wouldn’t have done about eighty percent of what Allie’d been up to lately even if she could have. Second circle, Allie’s circle, was by definition appallingly domestic and Charlie considered showing up in time for dinner to be quite domestic enough, thanks very much.

Not that there was something wrong in always showing up at the same place for dinner; Allie was one hell of a cook. All the Gale girls could cook—Charlie herself being the exception that proved the rule. Her sisters claimed that Charlie’s single attempt at lemon meringue pie still gave them citrus-themed nightmares. The grass never had grown back.

Attention caught by a familiar sound, Charlie glanced up at the loft over the garage and grinned. Auntie Gwen and Joe were home. Her grin broadened as the rhythm and intensity increased. Joe was full-blood Fey; he’d survive.

As Charlie crossed the small courtyard between the store and the garage, leaves rustled. All three of the dwarf viburnum in the center bed leaned toward her, creamy white flowers trembling.

She could step into the Wood right now. Step out anywhere she wanted to.

Anywhere.

This was where she wanted to be.

There was nothing wrong with that.

The back door to the Emporium was never locked. It stuck a little, though. The buzz now making the muscle in her right calf jump, Charlie jerked the door closed behind her, turned, caught sight of her reflection in the huge antique mirror hanging in the back hall and said, “I’m happy to see you, too, but I’ve never met Paul Brandt and I’m not double jointed.”

The mirror had belonged to Allie’s grandmother, Charlie’s Auntie Catherine. They’d found it up and running when Allie’d inherited the Emporium and, given that magic mirrors were rare on the ground, the odds were high Auntie Catherine had activated it. Problem was, she’d been banished from the city before providing an owner’s manual. Although they had no proof, what little evidence they had suggested that, for Auntie Catherine, the mirror had been a full orchestra. Metaphorically speaking. For the rest of them, it was more a twelve year old with a kazoo and a dirty mind. Almost literally.

Auntie Catherine was, like Charlie, one of the family’s Wild Powers, but if that had given her an edge with the mirror, Charlie couldn’t seem to get her own ducks in a row. The mirror reacted to her the way it reacted to everyone else—with juvenile lechery and vague affection. It reminded Charlie of Uncle Arthur, only without the persistent pinching.

Resting her palm against the mirror, fingers spread, Charlie watched as her reflection’s hair color cycled through various blues, reds, greens, purples, paused on the short cap of turquoise she currently wore, and finally finished with the dark blonde/golden brown that was the Gale family default.

“You’re right,” she sighed, suddenly very tired. “The hair’s become shtick.” She sagged forward until her whole body pressed against the glass and wondered, yet again, how Auntie Catherine had slid inside. What had she seen inside the mirror? Had she been Alice or the Red Queen?

Stupid question.

She’d been the Jabberwocky.

Because Auntie Catherine had done what every Gale with Wild Powers did. She’d gone Wild. The we know best of the aunties had become a much less restrained I know best and anything that made the aunties seem restrained, was pretty freakin’ scary.

In the mirror, Charlie’s reflection aged, hair graying, gray eyes darkening to auntie black.

“Yeah, I know.” She straightened, feeling every kilometer of the drive south from Fort McMurray in a retired school bus with no air-conditioning. Her reflection continued to lean against the inside of the glass. “You’re not going anywhere and I’ve still got plenty of time to work out how Auntie Catherine did it.”

Halfway up the back stairs, the door to the apartment on the second floor slammed open, slammed shut, and Charlie suddenly found herself facing a seriously pissed-off teenage boy—the smoke streaming out of his nostrils a dead giveaway of his mood. He rocked to a stop and glared, hazel eyes flashing gold, pale blond hair sticking out in several unnatural directions, wide mouth pressed into a thin line.

“Jack.”

“Oh, you’re back.”The smoke thickened. “Good.You can tell Allie I don’t have to put up with this stuff!”

“She’s making you listen to Jason Mraz again?”

“What?” He had to stop and think, rant cut off at the knees. Charlie gave herself a mental high five; she rocked at pissy mood deflection. “No! She thinks I’m helpless!”

“Does she? Well, she thinks Katy Perry is edgy, so . . .” Charlie shrugged, letting the wall hold her up for a while. “Where are you heading?”

“Flying!”

“It’s . . .” It was too much effort to look at her watch, so she settled for general and obvious. “. . . late.”

His eyes narrowed. “That’s what Allie said!”

“Yeah, but I’m not trying to stop you. Go. Fly.” She waved the hand not holding the guitar in the general direction of the back door. “It’s not like you can’t handle anything that sees you.”

“That’s what Graham said,” Jack admitted, the smoke tapering off.

“He’s smarter than he looks. Just try to handle it non-fatally, okay? I’ve had a long day, and you know Allie’ll make me come with her to deal with the bodies.”

“Bodies.” His snort blew out a cloud of smoke that engulfed his head and he stomped past, close enough Charlie could feel the heat radiating off him, but not so close she had to exert herself to keep from being burned. “Jack, don’t burn down the building,” he muttered as he descended. “Jack, don’t turn the Oilers into newts and then eat them. Jack, don’t eat anything that you can have a conversation with. This world sucks!”

He made an emphatic exit out into the courtyard, slamming the door with enough force that the impact vibrated past Charlie’s shoulder blades.

“Well . . .” Charlie lurched away from the wall’s embrace and up the remaining stairs. “. . . that explains why the door’s sticking.”

Jack loved hockey, although he thought it wasn’t violent enough. He’d spent his first season as an enthusiastic Calgary Flames fan, learning the unfortunate fact that enthusiasm wasn’t enough and devouring their opponents wasn’t allowed.

The new scorch mark on the apartment door came as no great surprise.

“Because he’s fourteen,” Allie was saying as Charlie let herself in, put down her guitar, and closed the door. “And we’re responsible for him.�

��

“He’s a fourteen-year-old Dragon Prince and a fully operational sorcerer.” Graham wasn’t visible, but the double doors to their bedroom were open, so Charlie assumed that Graham was out of sight in the bedroom. There were other, less mundane possibilities, but he’d probably sound a lot more freaked had Jack made him invisible, microscopic, or transformed him into furniture. Again. He’d made a surprisingly comfortable recliner. “There’s nothing out there that can hurt him.”

“You’re missing my point.” Even looking at the back of Allie’s head, Charlie could see her eyes roll. “He’s a fourteen-year-old Dragon Prince and a fully operational sorcerer.”

“That’s what I said.” Graham sounded confused.

Charlie snorted. “Dude, she’s not worried about Jack.”

Allie spun around and Charlie had a sudden armful of her favorite cousin. At five eight, Allie was an inch taller, but she was in bare feet and Charlie’s sneakers evened things out.

“Don’t you ever knock?” Graham asked, coming out of the bedroom, charms covering more skin than the shorts. Most of the charms were Allie’s, a couple were Charlie’s, and one was David’s. And wasn’t that interesting. “Never mind,” he continued, crossing toward her, “stupid question.”

He didn’t bother pulling Allie out of the hug, just wrapped his arms around both of them and squeezed. Graham wasn’t exactly tall—Charlie knew damned well he lied about being five ten—but he was strong. Even working full time at the newspaper, he’d managed to hang on to the conditioning his previous part-time position had required. Although, why an assassin needed muscle when the big guns did all the work, he’d never made clear to Charlie’s satisfaction.

“Did we know you were coming in tonight?” he asked, dropping a kiss on Charlie’s temple.

“I did,” Allie gasped, crushed between them. “Charlie, sweetie, you stink.” A judicious elbow broke Graham’s hold.

“Yeah, twelve hours on the highway in a bus without air-conditioning will do that.”

Graham snorted. “Even to a Gale?”

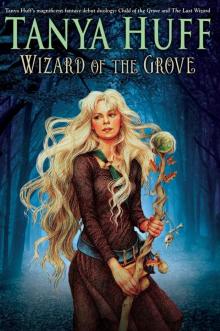

Child of the Grove

Child of the Grove Blood Lines

Blood Lines What Manner of Man

What Manner of Man Blood Pact

Blood Pact Blood Debt

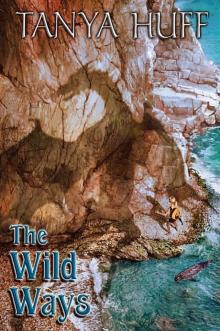

Blood Debt The Wild Ways

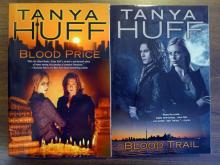

The Wild Ways Blood Trail

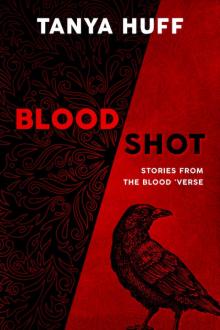

Blood Trail Blood Shot

Blood Shot Wizard of the Grove

Wizard of the Grove Valor's Trial

Valor's Trial The Privilege of Peace

The Privilege of Peace A Peace Divided

A Peace Divided Three Quarters

Three Quarters The Heart of Valor

The Heart of Valor No Quarter

No Quarter The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar

The Demon's Den and Other Tales of Valdemar Enchantment Emporium

Enchantment Emporium 3 Blood Lines

3 Blood Lines The Heart of Valour

The Heart of Valour Smoke and Ashes

Smoke and Ashes 2 Blood Trail

2 Blood Trail 1 Blood Price

1 Blood Price Summon the Keeper

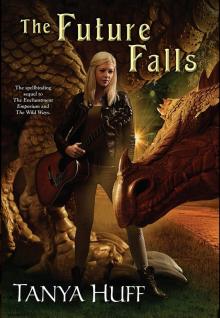

Summon the Keeper The Future Falls

The Future Falls Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World

Third Time Lucky: And Other Stories of the Most Powerful Wizard in the World The Second Summoning

The Second Summoning Fifth Quarter

Fifth Quarter The Enchantment Emporium

The Enchantment Emporium An Ancient Peace

An Ancient Peace Blood Bank

Blood Bank February Thaw

February Thaw The Better Part of Valour

The Better Part of Valour The Silvered

The Silvered Valour's Choice

Valour's Choice Smoke and Shadows

Smoke and Shadows Sing the Four Quarters

Sing the Four Quarters 4 Blood Pact

4 Blood Pact Long Hot Summoning

Long Hot Summoning The Better Part of Valor

The Better Part of Valor Scholar of Decay

Scholar of Decay He Said, Sidhe Said

He Said, Sidhe Said Wild Ways

Wild Ways Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light

Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light Valor's Choice

Valor's Choice Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan

Swan's Braid and Other Tales of Terizan